A Review of Difficult Airway Management Strategies in the Emergency Department

Gabrielle Michaeli, MD

Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine

In the emergency department, one of the most critical skills is airway management and performing intubation when necessary. The reasons for intubation vary but typically are a result of decreased or insufficient respiratory drive, an inability for the patient to clear secretions, or concern for impending airway compromise. Nearly 400,000 intubations occur in the emergency department each year.1 A large body of literature exists comparing different intubation techniques and the effects of adjuncts on successful intubation. One definitive finding is that higher attempt rates resulting in longer periods of apneic time are known to have deleterious effects on patients. For this reason, first pass success is a common surrogate for better clinical outcomes in many of these studies.

This article will focus on several different methods for airway management that have been studied to improve first pass success.

Video Laryngoscopy

By far, the most robust evidence exists for comparing direct laryngoscopy (DL) to video laryngoscopy (VL). Direct laryngoscopy involves direct visualization by the intubator during the procedure. Video laryngoscopy is an indirect method of visualization via a camera present at the end of the laryngoscope blade. Video laryngoscopes exist as standard geometry (curved or straight) blades or hyperangulated.

One study by Prekker et al. used an observation analysis of data gathered from the BOUGIE and PREPARE II trials analyzing the rate of first past success in DL versus VL. This study demonstrated that VL use produced superior views of the vocal cords and thus increased the rate of first pass success.2 A second study by Prekker et al. known as the DEVICE trial aimed to answer the same question. This prospective randomized control trial enrolled 1420 patients to either DL or VL over an 8-month period. Intubators were either emergency medicine residents or critical care fellows. First pass success was 85.1% in the VL group and 70.8% in DL. One weakness reported in this study is that the intubators had a higher rate of experience utilizing VL, possibly skewing results. Overall, however, this study further strengthened prior published data reporting higher first pass success in VL.3

A third study by Brown et al. utilizing data from the National Emergency Airway Registry adds that even when adding augmented positioning maneuvers such as ramped up body positioning, bougie, or cricoid pressure, VL without augmentation still outperforms DL with these maneuvers.4

Bougie

The bougie is a semi rigid stylet that is 60 cm long, 5 mm wide with a coudé tip. It is designed to easily pass through the vocal cords and is able to provide tactile feedback during intubations. There are many different versions of bougies that exist. To utilize the bougie, best practice is to insert your laryngoscope and pass the bougie as if it were an endotracheal tube. When passing the bougie, if you are able to continue passing it past the 50 cm mark, you are likely in the esophagus. If you are in the trachea, you will feel bumps from the tracheal rings and you will get tactile feedback when you hit the carina. When loading the endotracheal tube over the bougie, the laryngoscope should be kept in place to maintain tongue displacement.7

The BEAM trial was a single center RCT that randomized 757 patients to “bougie-first” intubation vs. standard intubation. First pass success occurred in 96% of the bougie-first patients compared to 82% of those undergoing standard intubation.8

The BOUGIE trial by Driver et al. was a multicenter randomized control trial that similarly randomized 1102 patients into a bougie-first intubation vs. standard intubation. Intubations were largely performed by fellows and residents. In this trial, first pass success was achieved 80.4% of the time in the bougie-first group and 83% in the standard intubation.9 This is quite a bit lower than in the BEAM trial, which begs the question if higher success occurred in the BEAM trial due to greater experience and comfort with the use of bougie during intubation.

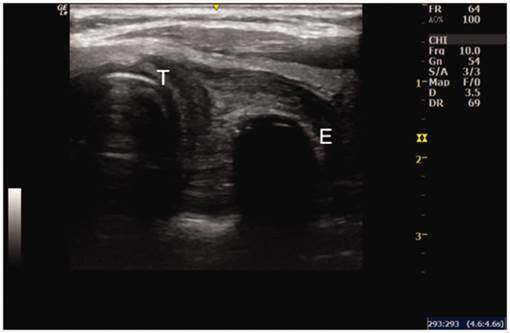

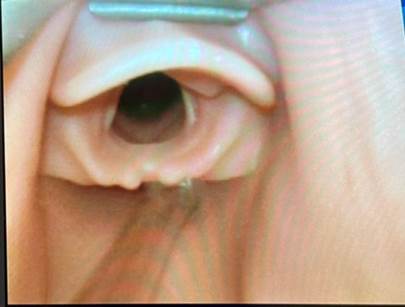

Ultrasound

The use of ultrasound in the emergency setting continues to grow. There are numerous ways to incorporate the ultrasound into daily practice. One use being investigated is for confirmation of endotracheal tube (ETT) placement. The current gold standard for tracheal confirmation is end-tidal capnography. However, in certain clinical scenarios, such as cardiac arrest, end-tidal is unreliable. Additionally, during an arrest, you are not able to obtain radiographic confirmation of ETT depth. As such, ultrasound is an ideal way to confirm ETT placement during critical situations.

An article by Gottlieb et al. discusses different ways to utilize point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for intubation. It assists with determining appropriate ETT depth by measuring the distance from the thyrohyoid membrane to the hyoid bone or epiglottis, as well as dynamically confirming endotracheal intubation or using multiple windows to confirm ETT placement.

To use ultrasound during intubation, more than one operator is needed. While intubating, you look for the “snowstorm sign.” This is described as a flutter of the tracheal rings that occurs when the tube makes contact with the trachea.

Following intubation, you can look for the “bullet sign” or the “double track sign.” The “bullet sign” shows rounding of the vocal cords due to the presence of the ETT. The “double track sign” is seen if there is esophageal intubation. The double track is seen because when the ETT is in the esophagus, there are two air filled lumens present.

Other surrogates for ETT placement include evaluation of lung sliding and diaphragmatic elevation, which can help evaluate for mainstem intubation. ETT depth has been evaluated by placing the probe at the sternal notch and looking for the ETT cuff. Studies have evaluated filling the cuff with saline to better visualize the cuff, although this is not standard practice in adults.

Ultrasound has also been utilized to better visualize the cricothyroid membrane to assist in cricothyrotomies.10

A randomized control trial by Hossein-Nejad et al. assessed the ability of emergency medicine residents to determine esophageal versus endotracheal intubation in cadavers utilizing ultrasound. Correct locations were determined 89.4% of the time.11

Long, Koyfman and Gottlieb performed a meta-analysis that showed ultrasound is 98.7% sensitive and 97.1% specific for determining endotracheal intubation. The meta-analysis included 17 studies. There was no demonstrated benefit in linear when compared to curvilinear probe choice. Ultimately, they report that this is user-dependent, and there is a learning curve to achieve the highest sensitivity and specificity.12

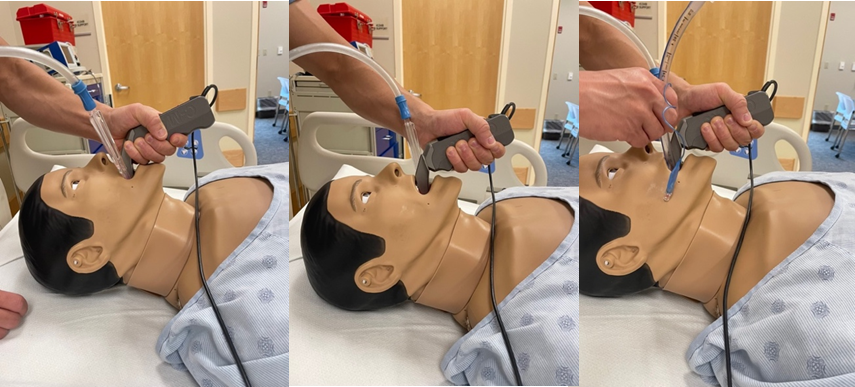

SALAD Method

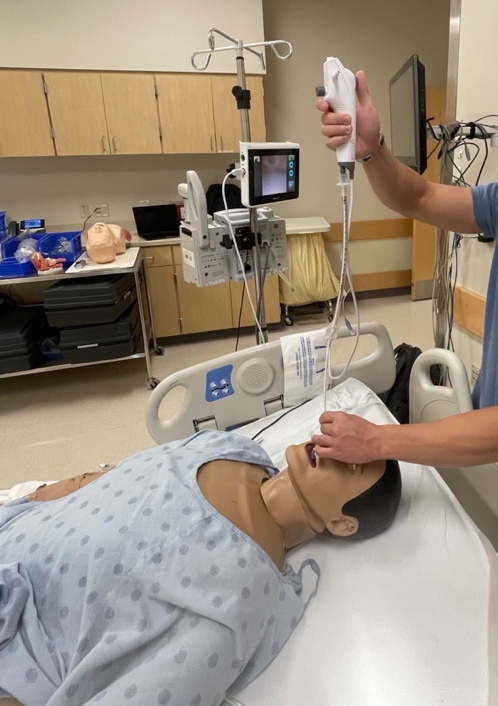

An important indication for intubation is large-volume emesis or hematemesis in an altered patient. Intubating in these scenarios can be challenging, given the presence of thick products that can obscure the view of the vocal cords. A proposed method to help combat this is known as the suction-assisted laryngoscopy assisted decontamination technique, otherwise known as the SALAD method. This was conceptualized by Dr. Jim Ducanto.

This method incorporates the use of a large bore suction catheter while performing intubation. During this technique, the suction catheter is placed into the mouth along with the laryngoscope. Once an adequate view is obtained, the suction is removed and subsequently replaced to the left of the blade into the esophagus known as the “SALAD Park Maneuver,” allowing for space for the ETT. A bougie or ETT is then inserted through the cords.14

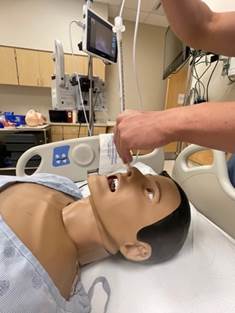

Fiberoptic

Fiberoptic laryngoscopy is becoming more prevalent in the emergency department, and single-use, disposable endoscopes are more readily available. Fiberoptic nasal intubation is beneficial in cases of angioedema, burns, trauma, foreign body aspiration, or other instances where intubating through the mouth is difficult. It is also useful in cases where awake intubation is preferred.17

In these cases, pharmacologic pretreatment is beneficial. These include:

- Glycopyrrolate or atropine to reduce secretions

- Ondansetron to reduce gag reflex

- Viscous lidocaine applied intranasally

- Nebulized lidocaine to anesthetize posterior oropharynx

- Ketamine or midazolam for anxiolysis

To perform nasal fiberoptic intubation, you will pretreat with the above medications. Next, you should evaluate both nostrils to determine patency, followed by preloading the endotracheal tube, typically a 7.0 or smaller, onto the endoscope. After the endoscope is inserted into the chosen nare, it is directed backwards and parallel to the transverse anatomic plane. Additional topicalization with aerosolized lidocaine may be required. Once past the nasopharynx, you will ideally have a direct view of the vocal cords. Once at the cords, spraying additional lidocaine onto the cords is often needed. At this point, the provider can then decide whether to administer parenteral sedation and/or a paralytic agent. When ready, the laryngoscope can be advanced through the cords. At this point, the endoscope may be used as a bougie, and the ETT can be passed through the nostril and then through the cords. Once past the cords, the laryngoscope can confirm the positioning, and the scope is then removed.18

In summary, there are a multitude of techniques that can be utilized for intubation. Overwhelmingly, literature favors the use of VL over DL. One important takeaway is there is a higher first pass success rate in method the operator has most practice with. Thus, in airways that you anticipate being difficult, use the methods and adjuncts with which you feel most comfortable.

References

- Maguire S, Schmitt PR, Sternlicht E, et al. Endotracheal Intubation of Difficult Airways in Emergency Settings: A Guide for Innovators. Med Devices (Auckl). 2023 Jul 18;16:183-99.

- Prekker ME, Trent SA, Lofrano A, et al. Laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation: does use of a video laryngoscope facilitate both steps of the procedure? Ann Emerg Med. 2023 Oct;82(4):425-31. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2023.02.016. Epub 2023 Apr 5.

- Prekker ME, Driver BE, Trent SA, et al. Video versus direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation of critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(5):418-429.

- Brown CA 3rd, Kaji AH, Fantegrossi A, et al. Video Laryngoscopy Compared to Augmented Direct Laryngoscopy in Adult Emergency Department Tracheal Intubations: A National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2020 Feb;27(2):100-108. doi: 10.1111/acem.13851. Epub 2020 Jan 20. PMID: 31957174.

- Azam S, Khan ZZ, Shahbaz H, et al. Video Versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Intubation: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2024 Jan 5;16(1):e51720. doi: 10.7759/cureus.51720. PMID: 38322075; PMCID: PMC10846758.

- Ruderman BT, Mali M, Kaji AH, et al. Direct vs Video Laryngoscopy for Difficult Airway Patients in the Emergency Department: A National Emergency Airway Registry Study. West J Emerg Med. 2022 Aug 19;23(5):706-715. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2022.6.55551. PMID: 36205675; PMCID: PMC9541990.

- Strayer, R. (2016b, February 1). Bougie every intubation. EM. https://www.emrap.org/episode/feb2016emrap/bougieevery

- Driver BE, Prekker ME, Klein LR, et al. Effect of Use of a Bougie vs Endotracheal Tube and Stylet on First-Attempt Intubation Success Among Patients With Difficult Airways Undergoing Emergency Intubation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319(21):2179-89. PMID: 29800096

- Driver BE, Semler MW, Self WH, et al. Effect of Use of a Bougie vs Endotracheal Tube With Stylet on Successful Intubation on the First Attempt Among Critically Ill Patients Undergoing Tracheal Intubation: A Randomized Clinical Trial.JAMA. 2021 Dec 28;326(24):2488-2497. doi: 1001/jama.2021.22002 PMID: 34879143

- Gottlieb M, Holladay D, Burns K, et al. Ultrasound for airway management: An evidence-based review for the emergency clinician. J Emerg Med. 2020 May;38(5)1007-13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.12.019.

- Hossein-Nejad H, Mehrjerdi MS, Abdollahi A, et al. Ultrasound for Intubation Confirmation: A Randomized Controlled Study among Emergency Medicine Residents. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2021 Feb;47(2):230-235. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.10.012. Epub 2020 Nov 18. PMID: 33218839.

- Long B, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound for Confirmation of Endotracheal Tube Placement. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 Sep;26(9)1096-1098. doi.org/10.11/acem.13773

- Chen W, Chen J, Wang H, et al. Application of bedside real-time tracheal ultrasonography for confirmation of emergency endotracheal intubation in patients in the Intensive Care Unit. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(4):030006051989477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060519894771. Epub 2019 Dec 27.

- Root CW, Mitchell OJL, Brown R, et al. Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD): A technique for improved emergency airway management. Resusc Plus. 2020 May 21;1-2:100005. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2020.100005. PMID: 34223292; PMCID: PMC8244406.

- Lin LW, Huang CC, Ong JR, et al. The suction-assisted laryngoscopy assisted decontamination technique toward successful intubation during massive vomiting simulation: A pilot before-after study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Nov;98(46):e17898. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017898. PMID: 31725637; PMCID: PMC6867733.

- Fiore MP, Marmer SL, Steuerwald MT, et al. Three Airway Management Techniques for Airway Decontamination in Massive Emesis: A Manikin Study. West J Emerg Med. 2019 Aug 6;20(5):784-90. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.6.42222. PMID: 31539335; PMCID: PMC6754197.

- Pirotte A, Panchananam V, Finley M, et al. Current Considerations in Emergency Airway Management. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2022;10(4):73-86. doi: 10.1007/s40138-022-00255-y. Epub 2022 Dec 3. PMID: 36531125; PMCID: PMC9734887.

- Nickson, C. (2020, November 3). Awake intubation. Life in the Fast Lane LITFL. https://litfl.com/awake-intubation/

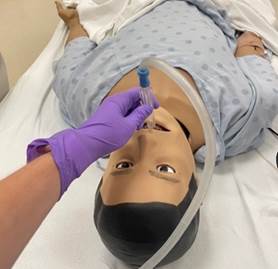

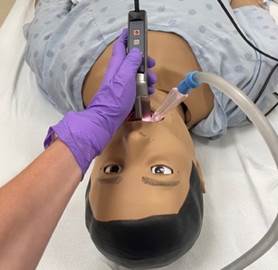

Salad Method

Figure 1: Introduce suction into patient oropharynx

Figure 1: Introduce suction into patient oropharynx

Figure 2: Insert laryngoscope

Figure 2: Insert laryngoscope

Figure 3: Switch suction to the left of the laryngoscope to allow room for the endotracheal tube or bougie

Figure 3: Switch suction to the left of the laryngoscope to allow room for the endotracheal tube or bougie

Figure 4: Suction tip at the proximal esophagus known as the "Park Maneuver"

Figure 4: Suction tip at the proximal esophagus known as the "Park Maneuver"

Figure 5: Suction in the "Park Maneuver" with appropriately placed endotracheal tube

Figure 5: Suction in the "Park Maneuver" with appropriately placed endotracheal tube

Other Option for SALAD Method Photos

Other Option for SALAD Method Photos

Fiberoptic Intubation Photos

Ultrasound