Pediatric Interscalene Nerve Block for Shoulder Dislocation and Reduction

Kaitlyn Boggs, MD

Ultrasound Fellow, Medical University of South Carolina

Aalap Shah, MD, FACEP

Ultrasound Fellowship Director, Medical University of South Carolina

Matthew M. Moake, MD, PhD

Director of Pediatric Emergency Ultrasound, Medical University of South Carolina

Case

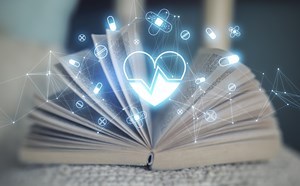

A 16-year-old male with history of recurrent shoulder dislocation and arthroscopic labral repair, presented with acute right shoulder pain after colliding with another player during basketball. The physical exam was notable for obvious right shoulder deformity, with an intact neurovascular exam. POCUS revealed an anterior shoulder dislocation without humeral fracture. After discussion with the family, the decision was made to proceed with an interscalene nerve block. The block was performed, and the shoulder was subsequently reduced successfully, confirmed by post-reduction POCUS (Figure 1). The patient was noted to have an asymptomatic ipsilateral diaphragm paralysis following the nerve block, which resolved within an hour, and he was discharged without complication. He did not require any opioids or procedural sedation throughout his ED stay, and tolerated both procedures well.

Figure 1. A) Pre-reduction anterior shoulder dislocation B) Post-reduction

Figure 1. A) Pre-reduction anterior shoulder dislocation B) Post-reduction

Background and Anatomy

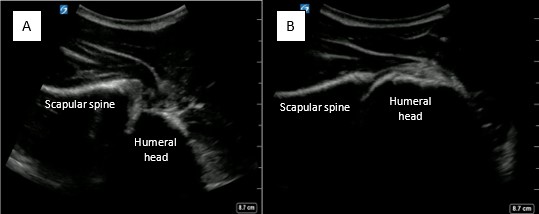

The brachial plexus gives rise to the C5-C7 nerve roots, which lay between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. This appearance is commonly referred to as a “traffic light sign.” In this view, major vessels of the neck should be medial to the target area (Figure 2). However, the dorsal scapular nerve and long thoracic nerve course through the middle scalene, and phrenic nerve passes along top of the anterior scalene.

The dermatomal distribution includes the shoulder and upper arm most reliably, the distal arm may be spared. This block also spares the medial aspect of the upper arm. The osteotome distribution includes the shoulder and humerus.

Figure 2. Interscalene nerve block anatomy, with the “traffic light sign” of C5-C7 nerve roots, situated between the anterior and middle scalene. The needle (emphasized in yellow) approaches the C5-C7 nerve roots from lateral to medial in-plane view.

Figure 2. Interscalene nerve block anatomy, with the “traffic light sign” of C5-C7 nerve roots, situated between the anterior and middle scalene. The needle (emphasized in yellow) approaches the C5-C7 nerve roots from lateral to medial in-plane view.

Positioning

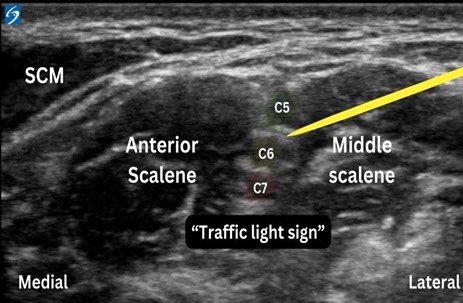

The patient is in the supine position with their head rotated to the contralateral side (Figure 3). If unable to tolerate a fully supine position, the patient may be semi-supine on the bed with towels to support the head and neck.

Figure 3. Interscalene nerve block needle approach.

Figure 3. Interscalene nerve block needle approach.

Equipment and Procedure

This procedure requires a high-frequency linear transducer, sterile probe cover and gel, chlorhexidine scrub, an 18 – 22 G blunt tip or spinal needle, and 10 – 15 mL of the local anesthetic of choice. For pediatrics or smaller patients, 0.3 – 0.5 mL/kg may be a sufficient suggested volume.

Place the transducer transversely above the clavicle to identify the subclavian artery and brachial plexus, then slide cephalad with the brachial plexus in view, until “traffic light sign” image appears. The needle should be inserted in-plane lateral to medial (Figure 2). The anesthetic should then be placed around the C5-C7 nerve roots within the interscalene groove. When administering anesthetic, the brachial plexus should be seen being pushed away from the middle scalene.

Complications

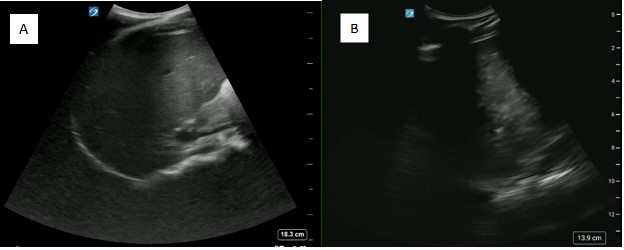

Ipsilateral hemidiaphragm paralysis is possible, as the phrenic nerve runs atop the anterior scalene muscle (Figure 4). Therefore, this block should be avoided in any patient with respiratory compromise, and a bilateral block should be avoided. Given the known complication of diaphragm paralysis, a short acting analgesic is suggested to avoid prolonged paralysis. Additionally, with any nerve block, careful consideration must be taken to account for maximum local anesthetic doses to avoid LAST.

Figure 4. Coronal FAST view that can be utilized to assess for ipsilateral diaphragm paralysis (A) and its resolution (B)

Figure 4. Coronal FAST view that can be utilized to assess for ipsilateral diaphragm paralysis (A) and its resolution (B)

Discussion

An interscalene nerve block is ideal for patients with shoulder dislocations. However, it can also be utilized with proximal humeral fractures, or any painful cutaneous procedure involving the shoulder and proximal arm, with the exception of the medial aspect of the upper arm/axilla. It is easily performed with quick analgesia necessary for shoulder reductions. Although multiple options exist for pain control for shoulder reduction, this block may be performed without opioid exposure or risk of sedation complications. Compared to an intra-articular injection, this will also provide more complete analgesia, and muscular relaxation which may aid in a reduction relocation attempts. Our patient in particular had had 5 prior shoulder reductions in the last two years. He had been previously reduced with sedation, intranasal opioids and intraarticular lidocaine injections of the glenohumeral joint. However, he stated this method was the “best one” in terms of comfort and ability to tolerate the relocation.

Ipsilateral hemidiaphragmatic paralysis is a known complication of interscalene nerve block that providers should expect to occur. However, it is tolerated well in a patient without known respiratory compromise or pre-existing respiratory conditions. This paralysis is temporary, so it is advisable to select a short-acting analgesic that is only required for the duration of the procedure. The presence of this complication can be confirmed with POCUS, in the traditional coronal FAST view. The resolution prior to discharge can also be confirmed with POCUS, as in this case (Figure 4).