Management of Non-Emergent Low Back Pain

Authors

- Jacob Basaleli DO

Emergency Medicine Resident, Northwell Health - Victor Huang MD, CAQ-SM

Sports Medicine Program Director, Northwell Health - R. Conner Dixon MD, CAQ-SM

Participant Physician, Emergency Medicine Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara

Case

24 year old male with a past medical history of hypothyroid who presents to the Emergency Department complaining of low back pain over the past two weeks. Patient reports returning from a snowboarding trip, and since that time has had severe intermittent low back pain which he describes as a stiffness which is worse with bending or walking. He reports radiation down the right lower extremity. He has attempted to take naproxen at home with minimal relief. Denies fevers, chills, weight loss, urinary retention, incontinence of bowel or bladder, saddle anesthesia, lower extremity weakness or numbness, and no recent trauma or falls. He has normal vitals and physical examination is normal except for paraspinal muscular tenderness and a positive straight leg raise. Motor and sensory examination is normal in both lower extremities.

Red Flags and Spine Emergencies (brief review)

In the emergency department, it is imperative to rule out any red flag signs/symptoms when obtaining a history and physical exam. This is important to screen for more emergent conditions such as a fracture, malignancy, hematoma, epidural abscess, cord compression, cauda equina syndrome etc. These are indications to obtain expedited imaging in the ED. Figure 1 is a decision support tool to guide imaging for patients with suspected red flag conditions.

It is also important to consider referred pain from other organs such as the thoracic (dissection, PE, pneumonia), abdominal (AAA, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, PUD, nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis) or pelvic organs (ie. prostatitis, PID,ovarian pathologies, endometriosis).

Red Flag Conditions and their Risk Factors or Symptoms:

- Infection / Spinal Epidural Abscess: recent spinal surgery or epidural injection, immunosuppression, IV drug user, fever, chills

- Tumor: history of malignancy, unexplained weight loss

- Cauda Equina Syndrome: bowel or bladder dysfunction, saddle anesthesia, sexual dysfunction, lower extremity neurological deficits

- Hematoma: anticoagulation, recent spinal surgery or epidural injection

- Fractures: history of trauma (like MVC or falls)

- Vertebral Compression Fracture: history of osteoporosis, chronic steroid use, elderly (> 65 years old)

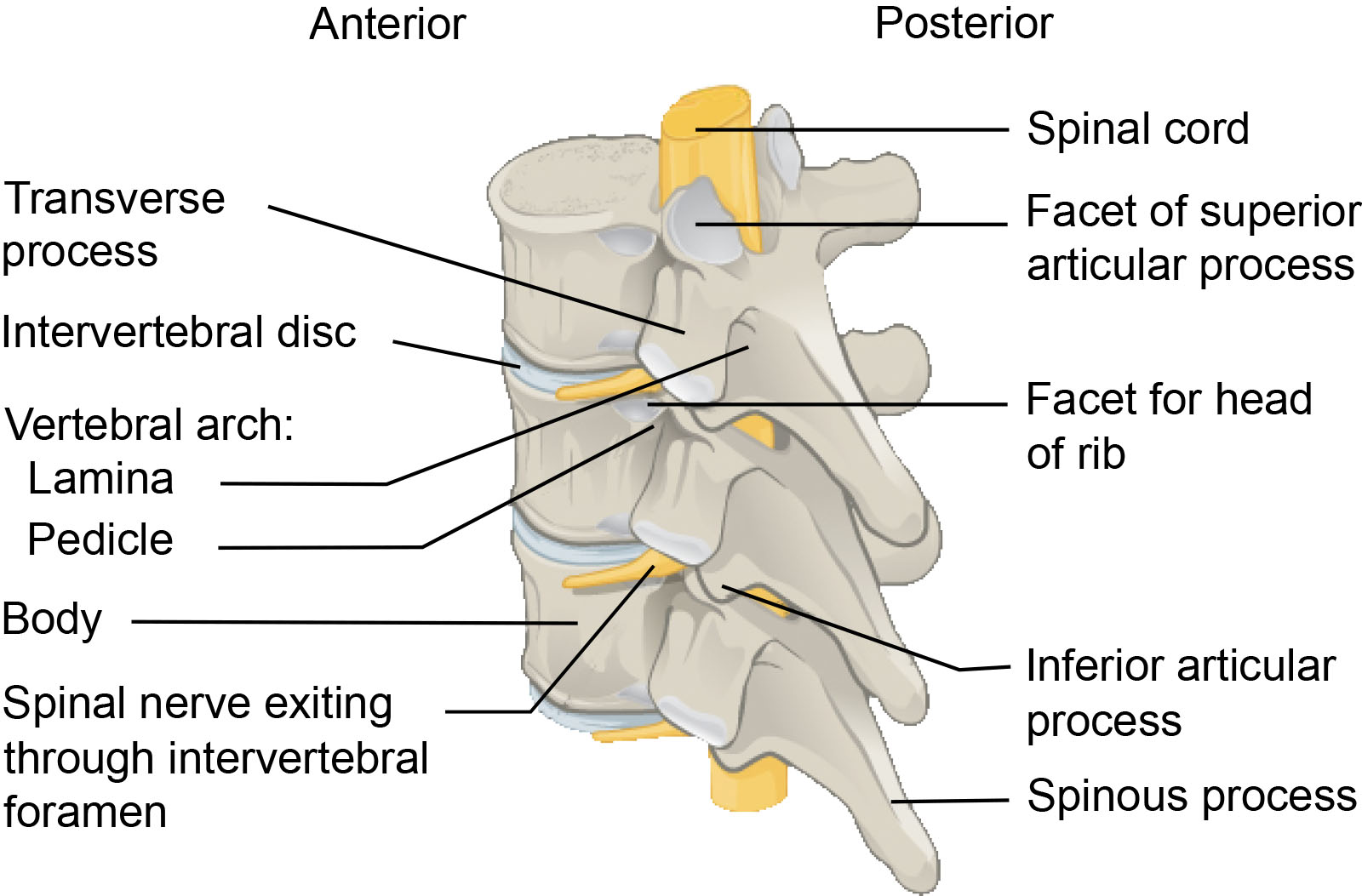

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- Vertebral Bodies: Vertebrogenic pain is caused primarily through pathological changes at the vertebral endplates. The vertebral endplates are highly innervated by the basivertebral nerve, which transmits nociceptive signals when the endplates are damaged or inflamed. Such damage can result from degenerative changes, trauma, intraosseous edema, or inflammation, leading to the proliferation of nociceptive fibers and increased pain sensitivity. This process is often associated with Modic changes seen on MRI: Type 1 (edema/inflammation), Type 2 (fatty infiltration), and Type 3 (sclerosis), with Type 1 and 2 changes being most closely linked to pain symptoms.

- Intervertebral Discs: Degeneration of intervertebral discs is a major contributor to lower back pain. Annular tears can cause pain directly, while disc herniation (rupture) can compress spinal nerve roots, leading to radicular pain (pain radiating down the leg). Loss of disc height alters spinal alignment and biomechanics, stressing facet joints. Chemical mediators released from a degenerated disc can also cause inflammation and pain.

- Facet Joints: Facet joint osteoarthritis, characterized by cartilage degeneration, inflammation, and bone spurs (osteophytes), is a common source of back pain. Osteophytes can also narrow the neural foramen, compressing the exiting nerve root and causing radicular pain. Increased load on facet joints due to disc degeneration can accelerate arthritic changes and pain.

- Paraspinal Muscles: Reduced muscle density, alterations in activation patterns, and fat infiltration of the paraspinal muscles are associated with lower back pain. These changes can impair spinal stability and motor control, contributing to pain and dysfunction. Muscle strains or spasms can also be a direct source of pain.

- Ligamentum Flavum: Hypertrophy (thickening) of the ligamentum flavum, often associated with aging and other degenerative changes, can contribute to spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal). This narrowing can compress spinal nerves, leading to back pain, radicular pain, and neurogenic claudication (leg pain with activity).

- Sacroiliac Joint Arthropathy: the sacroiliac joint is the cause of up to 25% of low back pain. This is the largest joint in the body and it lies between the sacrum and the ilium bones of the pelvis. The joint is relatively immobile and its primary function is to transfer weight to and from the lower limbs to the axial skeleton. There is a bimodal distribution in younger adults following injury and pregnancy as well as older adults from degenerative conditions. Patients typically present with pain in the buttock region that can extend down the posterior thigh and mimic radicular pain.

History

Onset and duration

- Acute < 4 weeks

- Subacute between 4-12 weeks

- Chronic > 12 weeks

- Mechanism of injury: traumatic vs atraumatic

- Characteristic and severity of pain

- Location/Radiation:

- Axial vs radicular: axial back pain is isolated to the lower back and may be due to myofascial pain, spondylosis, or issues with the facets and sacroiliac joints. Meanwhile, radicular pain refers to radiating pain down the leg and may be due to disc herniation and spinal stenosis.

- Aggravating and alleviating factors

- Flexion vs extension: differentiating which spinal movements exacerbate the patient’s symptoms can help identify the cause. For example, flexion-based movements can exacerbate symptoms from lumbar disc pathology like herniation. Extension-based movements can exacerbate symptoms from spinal stenosis and facet arthrosis.

- Stability or progression of symptoms

- Treatments attempted

- Neurologic symptoms

- Constitutional symptoms

- Impact on activities, work, sleep, etc

- Social and psychological factors

- Pertinent past medical/surgical history, family history and social history

Don't know if this section still has some details to fill out for things like onset, mechanism, etc. but I'm happy to do it if you want!

Physical Exam

- Inspection: assess for signs of trauma, asymmetry, swelling, and posture (lordosis, kyphosis, and scoliosis).

- Palpation: assess for tenderness to the midline over the vertebrae and the soft-tissue structures.

- Range of motion: flexion-extension, lateral flexion, and rotation.

- Special tests

- Neurodynamic assessments including straight leg raise (highly sensitive for disc herniation), seated slump test, and femoral stretch test.

- Sacroiliac joint: Fortin finger test, FABER (flexion-abduction-external rotation), Gaenslen test, distraction, compression, and thigh thrust

- Hip joint: log roll, scour test, and FADIR (flexion-adduction-internal rotation)

- Neurologic exam: sensation, motor, and reflexes

- Functional tests: observe for antalgic gait, Trendelenburg gait, and foot drop.

Diagnostic Testing

- Low back pain is classified as specific (pain and other symptoms that are caused by specific pathophysiological mechanisms of non-spinal or spinal origin) or nonspecific (back pain, with or without leg pain, without a clear nociceptive-specific cause). Diagnosis is on the basis of the exclusion of specific causes, usually by means of history taking and physical examination.

- Systematic reviews of observational studies have shown inconsistent findings with regard to the association between abnormal imaging findings and low back pain.

- Imaging is not routinely indicated in patients with nonspecific low back pain when there are no red flags. Most patients with an acute episode of nonspecific low back pain will recover in a short period of time.

- Subacute and chronic low back pain without red flags does not necessitate imaging unless the patient has failed 6 weeks of conservative therapy with both medical management and physical therapy. In these cases, MRI is the initial imaging modality of choice, but should be deferred to the outpatient setting.

- When patients have red flags discussed above and warrant imaging in the Emergency Department, there are several imaging modalities available including X-ray, CT and MRI.

- Plain Radiographs: X-ray imaging provides evaluation of bony spinal anatomy and pathology including fractures, spondylolisthesis, spondylolysis, etc. Screening for compression fractures can be performed with AP and lateral films. This imaging modality exposes patients to radiation, but it is readily available.

- Computerized Tomography (CT): CT scans provide detailed analysis of fractures, tumors, prosthetic loosening, and hardware fracture. Addition of IV contrast can be used to evaluate for epidural abscesses. This modality exposes patients to a significant amount of radiation.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is usually the gold standard in patients who require advanced spinal imaging because it provides greater distinction between different types of soft tissue, as well as the neurological elements of the spine. Addition of IV contrast can be used to evaluate for malignancy and infection, and it is also useful in patients who have had lumbar spine surgery as it distinguishes scar tissue from recurrent disc herniations. This imaging modality does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, but it is difficult to obtain in the ED.

Emergency Department Management

Pharmacologic modalities

For the emergency department management of low back pain, several pharmacologic options are available, each with varying degrees of efficacy and safety profiles.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): NSAIDs are commonly used as first-line treatment. A randomized controlled trial comparing ibuprofen, ketorolac, and diclofenac found no significant differences in pain relief among these NSAIDs, although ketorolac may result in less stomach irritation compared to ibuprofen. Another study indicated that NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen and diclofenac, are effective in reducing pain intensity. There are other longer-acting NSAIDs such as meloxicam that allow for once daily dosing. Choosing which NSAID to use is often based on familiarity to the prescriber and availability of the drug within your prescribing system.

- Acetaminophen: Acetaminophen alone has been shown to be effective for acute low back pain, with similar efficacy to NSAIDs and morphine in some studies. However, a Cochrane review found high-certainty evidence that paracetamol alone does not significantly reduce pain intensity compared to placebo for acute low back pain. With that said, there have been numerous studies comparing the efficacy of combination acetaminophen and ibuprofen (or other NSAIDs) with most showing an increased synergistic effect of the two.

- Opioids: Opioids like morphine can be effective for acute low back pain, particularly in cases of severe pain. However, their use is associated with a higher risk of adverse events, including nausea, constipation, and dizziness. The use of opioids should be limited to cases where other treatments are ineffective, and the potential benefits outweigh the risks. If at all possible, they should only be used for immediate pain control in the emergency department and not as a longer-term outpatient therapy.

- Skeletal Muscle Relaxants: Muscle relaxants such as baclofen, metaxalone, and tizanidine are often used in combination with NSAIDs. However, studies have shown that adding these muscle relaxants to NSAIDs does not significantly improve pain or functional outcomes compared to NSAIDs alone.

- Topical Treatments: Topical NSAIDs, such as diclofenac gel, have been evaluated for their efficacy in treating low back pain. A study found that topical diclofenac was less effective than oral ibuprofen and did not provide additional benefit when used in combination with oral ibuprofen.

Osteopathic Manipulative Therapy

- The American Osteopathic Association specifically recommends the use of certain OMT techniques for musculoskeletal causes of low back pain, based on systematic reviews and meta-analyses supporting their efficacy in reducing pain and improving function.

- Different types of osteopathic manipulative therapy (OMT) techniques commonly used for treating low back pain include:

- High-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) thrust: A direct, rapid manual technique applied to a specific joint to restore motion.

- Muscle energy technique (MET): A direct technique where the patient actively uses their muscles on request, from a precisely controlled position, in a specific direction, and against a counterforce.

- Strain-counterstrain (SCS): An indirect, passive technique that places the body in a position of maximal comfort to relieve tender points.

- Myofascial release (MFR): Can be direct or indirect; involves applying sustained pressure and stretch to the myofascial tissues to release restrictions.

- Soft tissue techniques: Involve stretching, deep pressure, and inhibition to relax hypertonic muscles and improve circulation.

Trigger point injection

- A myofascial trigger point is a discrete, hyperirritable spot located within a taut band of skeletal muscle that is painful on compression and can produce referred pain, motor dysfunction, and autonomic phenomena. These trigger points are a hallmark of myofascial pain syndrome (MPS), which is a common cause of both acute and chronic low back pain. Palpation of an active trigger point in the lumbar musculature can reproduce the patient’s low back pain and may elicit a local twitch response or referred pain pattern. Trigger points contribute to low back pain by generating persistent nociceptive input, leading to regional pain, muscle stiffness, and functional limitation. The diagnosis of MPS is clinical, based on the identification of taut bands, localized tenderness, and reproduction of the patient’s pain with palpation.

- Trigger point injections are a treatment in which a needle is inserted into the trigger point, often with local anesthetic or saline, to inactivate the trigger point and provide pain relief. The American Society of Pain and Neuroscience recommends trigger point injections for patients with myofascial low back pain that is refractory to conservative measures such as physical therapy and manual therapies.

Patient Education

- The majority of cases of acute low back pain are self-limited and will resolve with a short period of rest, typically within 4 weeks. It is important to promote early return to normal activities to preserve functional status. Relative rest and activity modification has been shown to be superior to bed rest, and prolonged bed rest may actually worsen symptoms. Patients can use low-level heat for 20 minutes at a time, every 2 hours followed with gentle stretches. Ice has not shown evidence of benefit, but it is not a harmful modality, so patients can utilize it if they get symptomatic relief.

- Lifestyle modifications including postural awareness, ergonomics, and proper lifting mechanics are also very important. For patients who sit while at work, they should maintain a lordotic lumbar spine curvature with both feet on the floor, neck aligned with the shoulders, and take frequent breaks to move and stretch. However, it is best to utilize a standing desk, as being upright puts less pressure on the intervertebral discs when compared to sitting, especially when they hunch forward. For those who perform manual labor, they should utilize proper lifting technique by bending at the hips and knees, keeping the back straight, and holding the object close to their body. Other important modifications include weight loss and regular exercise.

- Physical therapy programs can be initiated after the acute phase of low back pain. PT can improve pain, muscle spasm, posture, body mechanics, strength, flexibility, and functional status. It is most beneficial for subacute and chronic low back pain, but it can also minimize the risk of recurrent episodes and developing chronic symptoms.

Progressive Interventional Management

(brief overview of injections, implants, surgeries, etc). The most common interventional spine procedures for managing low back pain include:

- Epidural Steroid Injections (ESIs): Indicated for radicular pain due to herniated discs or spinal stenosis. ESIs can provide short-term pain relief by reducing inflammation around the nerve roots.

- Facet Joint Injections and Medial Branch Blocks: Used for diagnosing and treating facet joint pain, which is a common source of axial low back pain. These injections can help confirm the diagnosis and provide pain relief.

- Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA): Indicated for chronic facet joint pain. RFA involves the thermal destruction of the medial branch nerves that innervate the facet joints, providing longer-term pain relief compared to injections.

- Sacroiliac Joint Injections: Used for diagnosing and treating sacroiliac joint pain. These injections can help confirm the diagnosis and provide pain relief. These injections can be performed with image guidance with ultrasound or fluoroscopy.

- Percutaneous Disc Decompression: Indicated for patients with contained disc herniations causing radicular pain. Techniques include mechanical, thermal, or chemical decompression to reduce disc volume and alleviate nerve compression.

- Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS): Indicated for chronic, refractory low back pain, particularly neuropathic pain. SCS involves the implantation of a device that delivers electrical impulses to the spinal cord to modulate pain signals.

Recommendations from the Authors for a Quick Emergency Department Low Back Pain Encounter:

- We know that some encounters with patients for low back pain can be daunting due to patient expectations and difficulty with controlling pain. We propose a basic template below to help guide encounters to a more satisfactory outcome for both the patient and the provider. Many patients are more concerned about the unknown duration and cause of their pain rather than the acute pain itself. Being confident in your evaluation and management plan while counseling patients on next steps and how their pain will be managed both in and out of the emergency department can turn a frustrated patient encounter into smiles and thank yous.

- Evaluation

- Rule out the red-flag conditions first

- Perform a quick physical exam to determine the most likely pain generator (i.e. vertebra, disc, facet joints, radicular/nerve pain

- Pain Control

- Dealer’s choice but we recommend a combination of acetaminophen, NSAIDs (ibuprofen, ketorolac typically), and/or muscle relaxants or opiates depending on the severity of the presenting pain

- While we stated above that muscle relaxants don’t have any evidence for actually improving pain, they do act centrally and can “relax” the patient and relieve some of the anxiety around the pain which has its own value

- Opiates should be the last resort for outpatient management but depending on if the presenting pain is an acute exacerbation or if the patient has significant debilitating pain, opiates are always a choice the acute management of symptoms to break the pain cycle.

- Counseling

- This is where you can help your patients the most. Counsel them on the likely duration of their pain (or if it’s chronic already, ask what they have done to manage it outpatient). Give them the expected course and the next steps if one management course isn’t working (i.e. PT, MRI if pain isn’t improved, possible injections vs other procedures above, etc.)

- Follow-up

- Generally PCP follow up is a sufficient way to start

- If patients have difficulty seeing their PCP or if you think they should be at a different point in the therapy plan, referral to a spine specialist/physiatrist for evaluation and consideration of additional imaging/therapies is appropriate

References

- Shmagel A, Foley R, Ibrahim H. Epidemiology of Chronic Low Back Pain in US Adults: Data From the 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(11):1688-1694. doi:10.1002/acr.22890

- Meucci RD, Fassa AG, Faria NM. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review. Rev Saude Publica. 2015;49:1. doi:10.1590/S0034-8910.2015049005874

- Doo AR, Lee J, Yeo GE, et al. The prevalence and clinical significance of transitional vertebrae: a radiologic investigation using whole spine spiral three-dimensional computed tomographic images. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2020;15(1):103-110. doi:10.17085/apm.2020.15.1.103

- Malik K, Nelson A. Overview of low back pain disorders. Essentials of pain medicine. 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2018. P 193-206.

- Kinkade S. Evaluation and treatment of acute low back pain. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Apr 15;75(8):1181-8. PMID: 17477101.

- Alrazooqi MK, Skikic E, Iqbal SS, Sulaiman L, Muhammed Noori OQ. Traumatic Spinal Epidural Hematoma With Significant Neurologic Findings: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e38869. Published 2023 May 11. doi:10.7759/cureus.38869

- Horne JP, Flannery R, Usman S. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Feb 1;89(3):193-8. PMID: 24506121.

- Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging, Hutchins TA, Peckham M, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Low Back Pain: 2021 Update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(11S):S361-S379. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2021.08.002

- Hall A M, Aubrey-Bassler K, Thorne B, Maher C G. Do not routinely offer imaging for uncomplicated low back pain BMJ 2021; 372 :n291 doi:10.1136/bmj.n291

- Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jul 14;331(2):69-73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310201. PMID: 8208267.

- McDonald BT, Hanna A, Lucas JA. Spondylolysis. [Updated 2023 Aug 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513333/

- Devin CJ, McCullough KA, Morris BJ, Yates AJ, Kang JD. Hip-spine syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012 Jul;20(7):434-42. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-07-434. PMID: 22751162.

- Raj MA, Ampat G, Varacallo M. Sacroiliac Joint Pain. [Updated 2023 Aug 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470299/

- Morimoto T, Kobayashi T, Tsukamoto M, et al. Hip-Spine Syndrome: A Focus on the Pelvic Incidence in Hip Disorders. J Clin Med. 2023;12(5):2034. Published 2023 Mar 3. doi:10.3390/jcm12052034

- Benzon H, et al. Overview of Low Back Pain Disorders. Essentials of Pain Medicine. 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2018.

- Furman M, et al. Atlas of Image-Guided Spinal Procedures. 2nd edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2018.

- Wheeler S, et al. Evaluation of low back pain in adults. Uptodate.com. Published May 26, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2023.

- Kaji A. Thoracic and lumbar spinal column injury in adults: Evaluation. Uptodate.com. Published June 30, 2023. Accessed November 1, 2023.

- Kushner P, McCarberg BH, Wright WL, et al. Ibuprofen/acetaminophen fixed-dose combination as an alternative to opioids in management of common pain types. Postgraduate Medicine. Published online July 27, 2024:1-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2024.2382671

- Chou R. Subacute and chronic low back pain: Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment. Uptodate.com. Published July 18, 2023. Accessed November 1, 2023.

- Cashin AG, Wand BM, O'Connell NE, Lee H, Rizzo RR, Bagg MK, O'Hagan E, Maher CG, Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, McAuley JH. Pharmacological treatments for low back pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Apr 4;4(4):CD013815. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013815.pub2. PMID: 37014979; PMCID: PMC10072849.

- Sayed D, Grider J, Strand N, Hagedorn JM, Falowski S, Lam CM, Tieppo Francio V, Beall DP, Tomycz ND, Davanzo JR, Aiyer R, Lee DW, Kalia H, Sheen S, Malinowski MN, Verdolin M, Vodapally S, Carayannopoulos A, Jain S, Azeem N, Tolba R, Chang Chien GC, Ghosh P, Mazzola AJ, Amirdelfan K, Chakravarthy K, Petersen E, Schatman ME, Deer T. The American Society of Pain and Neuroscience (ASPN) Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline of Interventional Treatments for Low Back Pain. J Pain Res. 2022 Dec 6;15:3729-3832. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S386879. Erratum in: J Pain Res. 2022 Dec 24;15:4075-4076. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S402370. PMID: 36510616; PMCID: PMC9739111.

- Task Force on the Low Back Pain Clinical Practice Guidelines,. "American Osteopathic Association Guidelines for Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment (OMT) for Patients With Low Back Pain" Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, vol. 116, no. 8, 2016, pp. 536-549. Learn more here

- Franke, Helge et al. “Osteopathic manipulative treatment for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” BMC musculoskeletal disorders vol. 15 286. 30 Aug. 2014, doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-286

- Sayed D, Grider J, Strand N, et al. The American Society of Pain and Neuroscience (ASPN) Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline of Interventional Treatments for Low Back Pain [published correction appears in J Pain Res. 2022 Dec 24;15:4075-4076. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S402370.]. J Pain Res. 2022;15:3729-3832. Published 2022 Dec 6. doi:10.2147/JPR.S386879