Epistaxis in the Pediatric Emergency Department

Andrew Shieh, MD, CHOC Children’s Hospital, Orange, CA

Sarah Tomlinson, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

Epistaxis in children is often a self-resolving problem and is a common chief complaint in the emergency department.1 More than 50% of children under 10 years of age have nosebleeds. Most pediatric cases are idiopathic; other benign causes may include nose-picking, sinusitis, upper respiratory viral illnesses, allergic rhinitis, use of intranasal corticosteroids, and mucosal dryness.2 However, nosebleeds may also be the presenting symptom for children with inherited or acquired hematologic disorders, including immune thrombocytopenic purpura, von Willebrand disease, hemophilia and factor deficiency disorders, and Glanzman’s thrombocytopenia. Children taking anticoagulation and antiplatelet medications may also experience prolonged nosebleeds frequently.2 Additionally, spontaneous epistaxis is rare in children under 2 years of age, and an underlying coagulation disorder or non-accidental trauma should be considered.3

Children are often directed to the emergency department due to prolonged bleeding lasting over 30 minutes and the need for a detailed physical examination. Additionally, a history of hospitalization for nosebleeds, prior transfusions for epistaxis, or recurrent episodes of bleeding may require evaluation. Anterior rhinoscopy should be performed with an otoscope. In most cases, bleeding originates from the Kiesselbach plexus, a superficial network of small blood vessels, found in the anterior nasal septum. The nares should be inspected for possible foreign bodies. Careful examination may reveal anterior septal mucosal ulceration and bleeding, which suggests self-induced trauma from nose-picking behavior. Nasal turbinate hypertrophy or the presence of “boggy turbinates” can be a direct result of chronic inflammation caused by allergens and suggests allergic rhinitis. Bruising of the nasal bone or presence of a septal hematoma suggests recent trauma. Prominent nasal blood vessels are often fragile and can be easily irritated by nose-picking, dryness, or congestion. If other prominent blood vessels or spider veins (also known as telangiectasias) are noted elsewhere on the face, mouth, or tongue, Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome should be suspected. Unexplained bruising on examination may suggest non-accidental trauma or an undiagnosed bleeding disorder as the etiology.

A detailed interview of personal history, family history, and a thorough physical examination may elucidate symptoms consistent with possible oncological or bleeding disorders and calls for further workup, including laboratory studies and potential consultation with a hematologist. Von Willebrand disease is the most common inherited bleeding disorder and causes defective platelet adhesion at the site of injury. Epistaxis was the presenting symptom in 31% of children with this disorder, and 56% of children had prior nosebleeds in a cohort study of 113 children with von Willebrand disease.4 Immune thrombocytopenic purpura causes isolated reduced platelets, and nosebleeds has been identified as one of the most common symptoms in this cohort of children.5 If laboratory studies are pursued, a complete blood cell count (CBC), international normalized ratio (INR), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and type & screen should be obtained.

When a patient reports active bleeding in the emergency department, any concerns for airway compromise from bleeding into the oropharynx or hemodynamic stability due to blood loss should be addressed immediately. If there is only minor active bleeding without airway or hemodynamic issues, direct and sustained bidigital compression of the nasal ala against the septum (lower third of the nose) should be applied by the physician or caregiver for 20 minutes. The patient should be sitting with head flexed slightly forward in a “sniffing” position. A nose clip is an alternative to digital compression if the patient tolerates the device. If nosebleeds do not resolve with direct pressure alone, more urgent medical intervention is required for excessive bleeding. Vasoconstrictors including oxymetazoline can be applied by the clinician in conjunction with compression. Other antifibrinolytic medications can be applied by intranasal insertion of cotton or gauze impregnated with these medications, especially if the exact origin of the bleeding cannot be identified. If these interventions do not stop bleeding, non-resorbable packing including gauze dressings and inflatable ballons may be used. This type of packing must be removed after sustained control of hemorrhage is achieved. However, duration of placement varies due to severity and comorbidities, ranging from 4 to 48 hours or even longer. Resorbable materials include oxidized regenerated cellulose (ie, Surgicel), hemostatic gelatin thrombin matrices (ie, Floseal, Surgiflo), and others. Use of resorbable packing instead of non-resorbable packing generally is recommended in children with bleeding disorders, those currently taking anticoagulation medications, and younger children, as removal of packing can lead to mucosal trauma and additional bleeding. The use of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis with nasal packing to prevent toxic shock syndrome is controversial. All patients who are evaluated in the emergency department should be followed by a medical physician within 24 to 48 hours for non-resorbable packing removal, if packing was used, and reexamination to ensure complete dissolution of bleeding and proper healing of nasal mucosa.

Nearly all uncomplicated epistaxis will be resolved as children get older. Pediatric epistaxis rarely leads to long-standing complications and most children can resume normal activities shortly after treatment. Recommendations for children who have been treated with cauterization, packing, or other procedural interventions should be made on an individual basis.

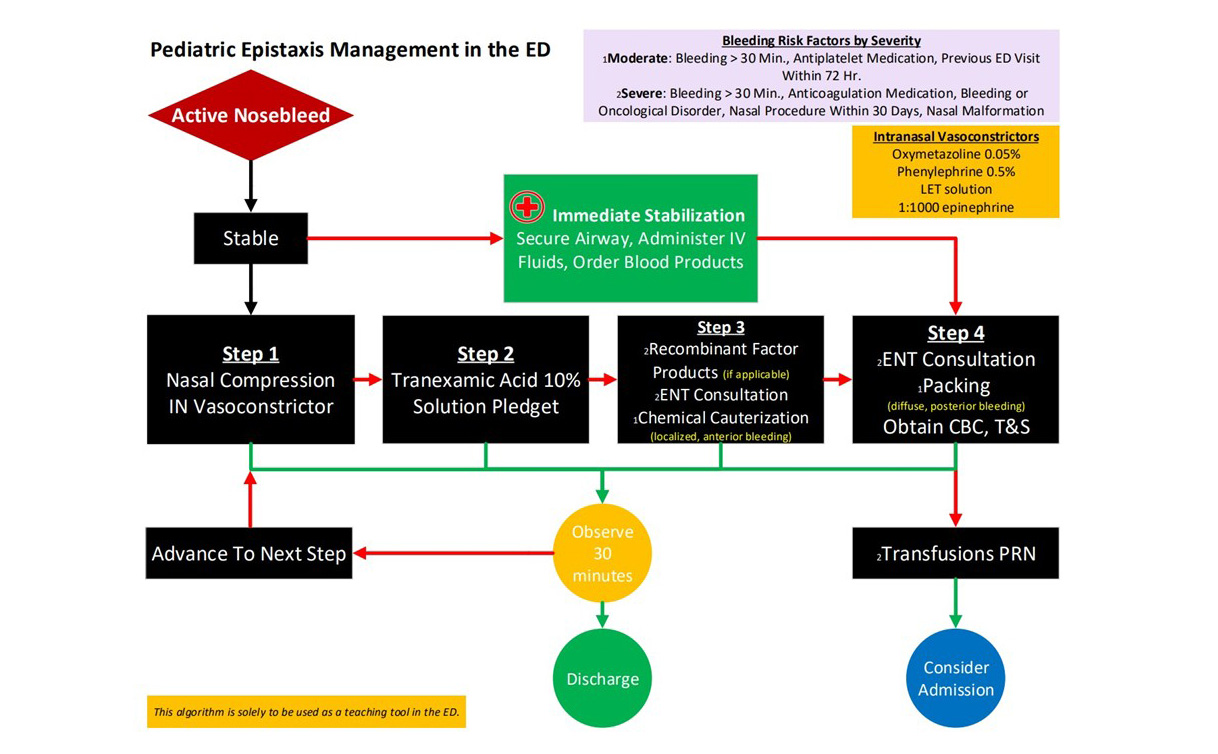

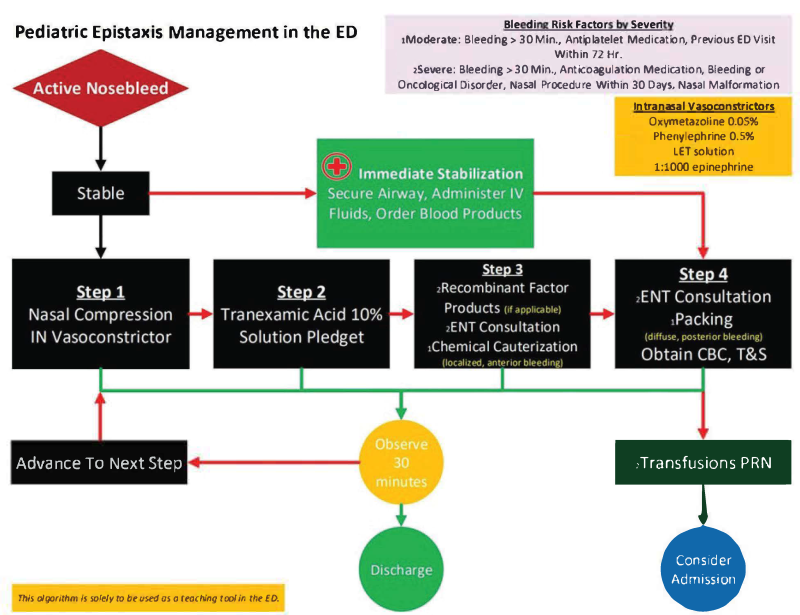

We have included an algorithm below highlighting an approach to managing epistaxis in children with active bleeding who present to the emergency department and may not apply to all emergency departments and clinical scenarios; it should be used as educational material only for medical professionals.

Acronyms: CBC: complete blood cell count; IN: intranasal; LET: lidocaine, epinephrine, tetracaine; T&S: type & screen.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Weyand, a pediatric hematologist at the University of Michigan, and Dr. Bohm, a pediatric otolaryngologist at the University of Michigan, for their input on this algorithm.

References

- Shay S, Shapiro NL, Bhattacharyya N. Epidemiological characteristics of pediatric epistaxis presenting to the emergency department. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017; 103:121-124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.10.026

- Shieh A, Cranford JA, Weyand AC, Bohm LA, Tomlinson SE. Risk Factors and Management Outcomes in Pediatric Epistaxis at an Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2024;66(2):97-108. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2023.10.031

- DeLaroche AM, Tigchelaar H, Kannikeswaran N. A Rare but Important Entity: Epistaxis in Infants. J Emerg Med. 2017;52(1):89-92. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.07.079

- Sanders YV, Fijnvandraat K, Boender J, et al. Bleeding spectrum in children with moderate or severe von Willebrand disease: Relevance of pediatric-specific bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(12):1142-1148. doi:10.1002/ajh.24195

- Reynolds L, Williams BD, Grainger J. Epistaxis duration predicts bleeding in immune thrombocytopenia: a cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2022;107(12):1117-1121. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2021-323064