When The Bowel Folds Inside Itself

Andrew Shieh, MD

CHOC Children’s Hospital, Orange, CA

Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children and occurs when a portion of bowel telescopes and invaginates inside an adjacent segment. It is the most common abdominal emergency in early childhood. It is typically seen in children between 3 months and 3 years old, with a peak incidence prior to 9 months old, and occurs four times more in boys compared to girls.1–3 Classic childhood intussusceptions are predominantly ileocolic in nature (90% of cases), while small bowel intussusception is uncommon in children as compared with adults.4 If the mesentery telescopes together with the bowel, bowel ischemia may occur.

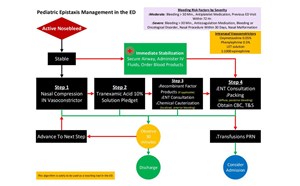

When should intussusception be suspected?

Most episodes occur in healthy children with no significant abdominal discomfort on physical examination. Intermittent colicky abdominal pain and emesis (may become eventually bile-stained) are common symptoms for all cases. The pain is classically described as sudden onset, intermittent, crampy, and progressive, accompanied by crying and drawing of the knees toward the abdomen. A sausage-shaped mass is rarely palpated in the right mid or upper abdomen. These symptoms mimic gastroenteritis or appendicitis, and the diagnosis can be missed if imaging is not obtained, or if intussusception spontaneously resolves prior to diagnostic imaging. Late symptoms include lethargy, currant jelly stool, and severe abdominal pain (due to peritonitis or intestinal necrosis).5 Children with ileocolic intussusception have more severe clinical symptoms, with recurrent vomiting, blood in stool if present, and leukocytosis (if laboratory testing is obtained) compared to those with small bowel intussusception.1

Who is at risk for intussusception?

Intussusception can be categorized as secondary to a pathologic lead point, by anatomic location, or idiopathic. The cause is often not known, although recent viral infections, specifically gastroenteritis, cause Peyer’s patches (lymphoid tissue in the small intestine) to hypertrophy and are associated with some occurrences. Structural abnormalities (polyps, duplication cysts, tumor, vascular malformation), Meckel’s diverticulum, and recent intestinal surgeries may act as lead points.6 In children with IgA vasculitis, a small bowel wall hematoma can act as the lead point. A pathologic lead point is more likely to be present in older children. Other chronic conditions associated with intussusception include cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease. In most children, the cause is unknown, while in adults, a pathological cause often is identified.

How is intussusception diagnosed?

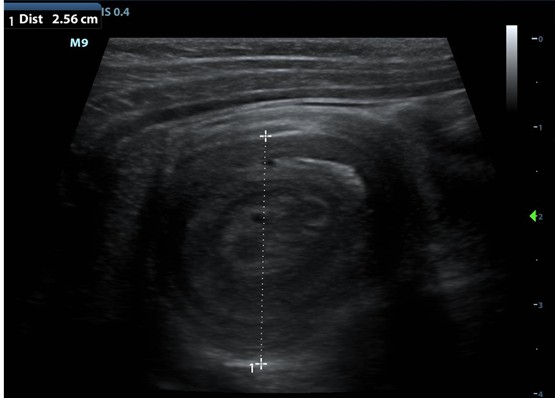

Patients do not need to be nothing by mouth (NPO) for diagnostic imaging. Abdominal ultrasonography is the first-line tool for diagnosis, as it is highly sensitive and specific. A complete examination includes evaluation of the entire abdomen in both longitudinal and transverse planes with a linear array transducer. In general, true ileocolic intussusception is positive when the classic target sign is over 2.5 cm in diameter and is found in the right side of the abdomen. It may include lymph nodes and mesenteric fat. Small bowel intussusceptions typically have a mean diameter of less than 2 cm.1,2 Occasionally, it can be difficult to differentiate between ileocolic and small bowel intussusceptions, as both may measure between 2 and 3 cm in size on ultrasound and as a doughnut-like lesion. In questionable cases, repeat ultrasonography after 20 minutes should be obtained to investigate whether the intussusception has resolved, as ileocolic intussusceptions are unlikely to self-resolve. Color duplex over the targetoid structure can suggest development of bowel ischemia if a lack of perfusion is seen. Computed tomography scan has been reported to be highly sensitive and specific in the diagnosis small bowel intussusceptions and can be helpful to identify pathologic lead points, but is time-consuming and exposes children to radiation.4,6

Figure-Ultrasound suggestive for ileocolic intussusception with a classic target sign, also termed “bull’s eye.”

How is intussusception treated?

If not treated, intussusception can lead to bowel necrosis, ischemia, and potentially death. Therapeutic options for ileocolic intussusceptions include reduction with fluoroscopic air enema or contrast enema. Pneumatic reduction is more likely to be successful compared to contrast reduction, and the main risk, albeit low, is bowel perforation.3 Laparoscopic surgery is reserved for patients with concern for bowel perforation, hemodynamic instability, and failure of enema reductions after multiple attempts. The presence of bloody stool, by itself, is not a contraindication to attempt nonoperative reduction. If reduction is partially successful, another attempt can be made. Most cases of small bowel intussusception in children with minimal symptoms require expectant management to allow spontaneous reduction. However, it is important to ensure the intussusception resolves, as up to 3% of children may eventually require surgery.6 Patients with small bowel intussusception caused by pathologic lead points are more likely to require surgery.6

Can intussusception recur?

Healthy children who undergo successful reduction are unlikely to experience complications.7 Children should be observed in the emergency department for at least 4 hours for recurrent pain and vomiting. Prior studies suggest early recurrence within 48 hours after successful reduction occurs in 2.5% to 13% of cases in some institutions.7,8 Potential clinical risk factors associated with early recurrence includes fever and female sex.8 No radiologic findings are associated with recurrence.8 Absolute criteria for inpatient admission includes failure to tolerate oral fluids and more than 3 reduction attempts. If patients are still well appearing after a brief period of observation, parents should be instructed to bring their child back to the emergency department promptly for repeat ultrasound if the child has a recurrence of symptoms.

References

- Lioubashevsky N, Hiller N, Rozovsky K, Segev L, Simanovsky N. Ileocolic versus small-bowel intussusception in children: can US enable reliable differentiation? Radiology. 2013;269(1):266-271. doi:10.1148/radiol.13122639

- Wiersma F, Allema JH, Holscher HC. Ileoileal intussusception in children: ultrasonographic differentiation from ileocolic intussusception. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(11):1177-1181. doi:10.1007/s00247-006-0311-2

- Beres AL, Baird R. An institutional analysis and systematic review with meta-analysis of pneumatic versus hydrostatic reduction for pediatric intussusception. Surgery. 2013;154(2):328-334. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.036

- Ko SF, Lee TY, Ng SH, et al. Small bowel intussusception in symptomatic pediatric patients: experiences with 19 surgically proven cases. World J Surg. 2002; 26(4):438-443. doi:10.1007/s00268-001-0245-7

- Huang HY, Huang XZ, Han YJ, et al. Risk factors associated with intestinal necrosis in children with failed non-surgical reduction for intussusception. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017;33(5):575-580. doi:10.1007/s00383-017-4060-0

- Koh EPK, Chua JHY, Chui CH, Jacobsen AS. A report of 6 children with small bowel intussusception that required surgical intervention. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(4):817-820. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.12.028

- Bajaj L, Roback MG. Postreduction management of intussusception in a children’s hospital emergency department. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 Pt 1):1302-1307. doi:10.1542/peds.112.6.1302

- Vo A, Levin TL, Taragin B, Khine H. Management of Intussusception in the Pediatric Emergency Department: Risk Factors for Recurrence. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36(4): e185-e188. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001382