Ulnar Nerve Block

Andrew Butki, DO

Leonard V. Bunting, MD, FACEP

I. Overview and Indications

- Ultrasound guided regional anesthesia performed in the ED by emergency physicians is being performed at most academic EDs.1

- Nerve blocks of the forearm are safe and provide an effective alternative to sedation and opioid analgesics for pain management in the ED with high levels of satisfaction among both patients and physicians.2-4

- Forearm nerve blocks should be considered as an alternative to digital nerve blocks; the duration can be much longer, and it doesn’t require the pain, pressure or distortion of injecting into the finger’s small volume.

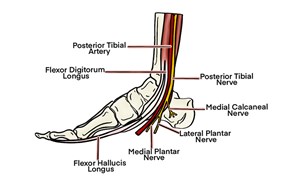

- There is overlap of the hand’s sensory territory.

- The ulnar nerve provides innervation to the ulnar/medial palm, but provides exclusive innervation to only a small area of the pinky finger.5

- Consider providing blockade of ulnar, median, and/or radial nerves for most injuries.6

Indications

- Lacerations, burns, abscesses, foreign bodies, or any soft tissue injury to the ulnar surface of the hand and wrist

- Isolated 5th metacarpal fractures

- Forearm nerve blocks in general are not as useful for fractures of the wrist. Generally, the innervation of the bones (osteotomes) follow their own pattern that does not coincide with the innervation of the skin or more superficial structures (dermatomes).7

Contraindications

Illustration 1. Distribution of anesthesia

II. Equipment

- Probe selection: 6-12 MHz linear transducer

- Sterile transparent film dressing (ie, Tegaderm™) or sterile probe cover

- 7-10 mL of anesthetic of choice

- 27-gauge needle for skin wheal with syringe of 2-3 ml of lidocaine with epinephrine

- 20-22-gauge needle, 1.5 inch or longer (Needle choices) depending on body habitus

III. Setup and Patient Positioning

- General procedure setup

- Patient sitting upright

- Forearm supine and abducted, externally rotated to your and patients’ comfort

IV. Pre-scan/Sonographic Anatomy

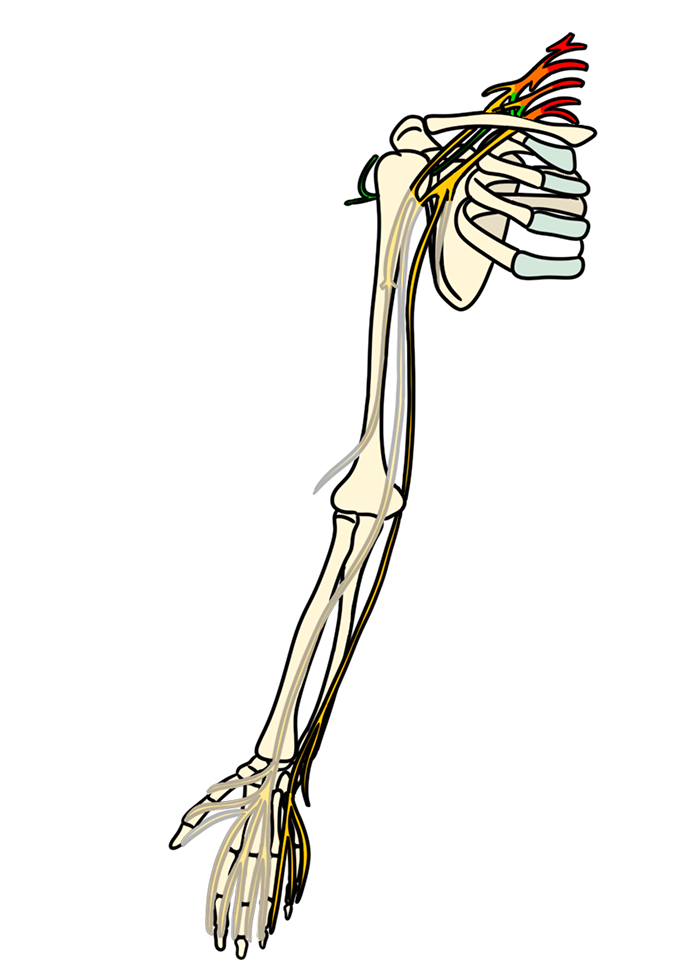

Anatomy

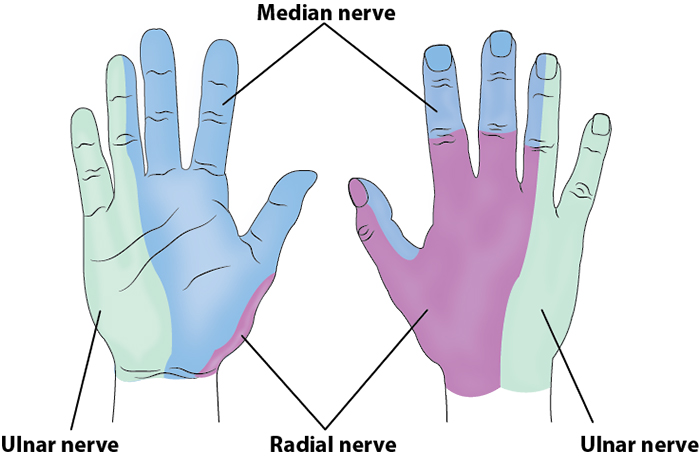

- The ulnar nerve runs down the forearm ulnar (medial) to the ulnar artery.

- It enters the forearm by passing posterior to the medial epicondyle of the humerus (cubital tunnel) and descends between the flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus muscles until it passes through the ulnar canal (Guyon canal) into the hand.8

- In the forearm it lies in the same neurovascular fascia layer as the ulnar artery.

- At the level of the wrist, it is nearly adjacent to the artery.

- In the proximal forearm there is a greater separation between the ulnar artery and nerve.

Illustration 2. Course of the ulnar nerve

Pre-scan

- Place the probe transversely on the volar surface of the forearm.

- Slide the probe medially to identify the pulsatile ulnar artery.

- Directly medial (ulnar side) to the ulnar artery should be a hyperechoic structure representing the ulnar nerve.

- The nerve can be oval or triangular.

- The ulnar nerve sits in the same echogenic fascial plane as the artery.

- If not immediately seen rapidly slide up and down the ulnar artery to identify the nerve associating with the artery.

Video 1. Ulnar nerve pre-scan

Figure 1. Sonographic appearance of the ulnar nerve in the mid forearm

V. Procedure

The in-plane approach is recommended, but other approaches are possible.

- Out-of-plane

- This approach is helpful if the patient can’t externally rotate their arm enough to allow an in-plane approach.

- An out of plane approach can separate a tightly associated ulnar nerve and artery.

- Above the elbow

- Before entering the cuboid tunnel from the upper arm, the ulnar nerve is very superficial and amenable to in-plane blockade.

- Positioning for this approach may be difficult for patients with limited mobility or significant trauma.

In-plane Approach Procedure

- Use standard sterile skin preparation.

- Cover probe using sterile transparent film dressing (ie, Tegaderm™) or sterile probe cover.

- Flush all needles of air as air obscures ultrasound imaging.

- Create skin wheal using a 25-30-gauge needle.

- Insert your block needle 5mm at the short side of the probe with bevel pointing upwards.

- Visualize the needle.

- Ensure your needle path avoids arterial puncture.

- Aim for the bottom of the nerve.

- This helps avoid injuring the nerve.

- Injected fluid will naturally push superficially, following the path of least resistance.

- Advance until you achieve “mechanical coupling,” where the blunt portion of your needle is in direct contact with the nerve and movement of the needle causes movement of the nerve.

- Inject a test of 0.5mL of anesthetic to confirm location.

- Follow general injection precautions.

- If you are appropriately within the perineural space, your anesthetic will envelop the nerve and seem to push the nerve away from the needle.

- If you are not close enough your anesthetic will create a bolus of anesthetic directed away from the nerve.

- Once appropriate placement is confirmed, inject the remainder of the anesthetic until you have enveloped the nerve on at least 3 sides (preferably all sides).

- It is imperative that anesthetic is seen between the ulnar nerve and artery.

- Typical volumes required are 5-10 ml.

Figure 2. Hands for the out-of-plane ulnar nerve block

Video 2. In-plane ulnar nerve block

Out-of-plane Approach Procedure

- The target of the out-of-plane approach is either side of the ulnar nerve.

- Injecting between the artery and nerve is most likely to achieve good anesthetic spread but can be challenging.

- Consider injecting along the medial surface of the nerve first to dissect the fascial planes and then redirect as needed to the nerve/artery border.

- After skin anesthesia, center the target on the image and insert the block needle 3 mm at a 45-degree angle to the skin at the center of the long side of the probe.

- Slide the probe toward the needle tip until the tip is seen (Visualizing the needle).

- Once the needle tip is seen, move the probe and needle in the stepwise fashion outlined in the out-of-plane section here down toward the target.

- Once the needle tip is adjacent to the target, inject 0.5cc of anesthetic.

- Follow injection precautions.

- If the anesthetic flows around the nerve, continue to inject in 1 cc increments until the nerve is surrounded and the block volume is reached.

- If the anesthetic is seen outside the perineural space, redirect the needle and inject another 0.5 cc.

- Readjustment of the needle position may be necessary to achieve adequate distribution of anesthesia.

- Always perform aspiration and incremental injection to avoid systemic distribution of the anesthetic.

- Typical block volumes are 5–10 cc.

- Full block onset may take up to 15–20 minutes, particularly if a long-acting anesthetic was used.

Above the Elbow Approach Procedure

- With the patient’s shoulder abducted and either maximally internally or externally rotated, obtain a transverse image of the cuboid tunnel at the medial epicondyle.

- Slide the probe proximally 1-3 cm and identify the ulnar nerve in the superficial soft tissue.

- Block at this level using the in-plane approach described above.

VI. Post-procedure Care

Consider marking on skin with skin pen the time and date of block performed.

VII. Pearls and Pitfalls

- Inadequate anesthesia may result from blockade of the ulnar nerve alone. Consider blocking two or all three forearm nerves, as there is overlap in the regions covered by each nerve.

- All nerves display anisotropy (ie, the nerve is significantly more visible when your probe is perfectly perpendicular to the nerve). Fanning your probe as you scan up and down the forearm can improve visualization of the ulnar nerve.

- Too short or too thin a needle will make needle progression difficult, especially in a patient with very large or muscular forearms.

- The most painful part of the procedure is the initial skin puncture, which is why a small local anesthetic skin wheal is recommended

- The majority of the needle path is through musculature, which is usually well tolerated by patients (skeletal muscle fibers themselves do not receive direct innervation by free Type C nerve endings).8

- Usually 5-7mL of anesthetic is required, and systemic toxicity is unlikely. However, if multiple blocks are performed (median, ulnar, and radial nerve) it is possible to approach or even cross the threshold for toxicity.

VIII. References

- Richard A, Jeffrey K, Arun N, Srikar A. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks in emergency medicine practice. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35(4):731-6.

- Nejati A, Teymourian H, Behrooz L, Mohseni G. Pain management via ultrasound-guided nerve block in emergency department; a case series study. Emerg (Tehran). 2017: 5(1):e12.

- Bhoi S, Rodha M, Ramchandani R, Sinha T, Bhasin A, Galwankar S. Feasibility and safety of ultrasound-guided nerve block for management of limb injuries by emergency care physicians. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5(1):28-32.

- Liebmann O, Price D, Mills C, Gardner R, Wang R, Wilson S, et al. Feasibility of forearm ultrasonography-guided nerve blocks of the radial, ulnar, and median nerves for hand procedures in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:558-62.

- Mackinnon S, Fox I, et al. Peripheral nerve surgery: A resource for surgeons. Washington University School of Medicine, 2010.

- Frenkel O, Herring AA, Fischer J, Carnell J, Nagdev A. Supracondylar radial nerve block for treatment of distal radius fractures in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(4):386-8.

- Carrera A, Lopez A, Sala-Blanch X, et al. Functional Regional Anesthesia Anatomy. New York School of Regional Anesthesia.

- Moore K, Dalley, A. Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2006.

IX. Additional Reading

Mense S, Gerwin R. Muscle Pain: Understanding the Mechanisms. Springer 2010. ISBN: 978-3-540-85020-5.